The "gay cake" case - guest post on Lee v the UK

Lee v the United Kingdom - guest post by Dr. Silvia Falcetta, University of York

The Fourth Section of the European Court of Human Rights has published its decision in the case of Lee v the United Kingdom.

This case concerns the refusal of a bakery, the Ashers Baking Company Limited, and its Christian owners to provide the applicant with a cake with the words ‘Support Gay Marriage’ iced on it.

The Court declared the application inadmissible by a majority on the grounds of non-exhaustion of domestic remedies.

Facts of the case

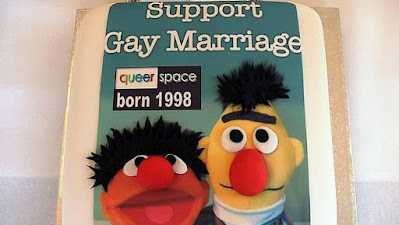

In May 2014, the applicant, Mr Gareth Lee, decided to order a cake from a bakery, Ashers Baking Company Limited (‘Ashers’), with a picture of two popular characters from a children’s television show, the logo of 'QueerSpace' (an LGBTIQ organisation the applicant is associated with) and the words ‘Support Gay Marriage’. Mr Lee’s order was received without comment, he paid for and received a receipt for his purchase. However, a few days later he received a telephone call from Ashers in which they explained that they were a Christian business and that they should not have taken the order.

With the support of the Equality Commission for Northern Ireland, Mr Lee brought an action in the County Court for breach of statutory duty in and about the provision of goods, facilities and services against Ashers, as a limited company, and its owners, Mr and Mrs McArthur (‘the McArthurs’). Mr Lee claimed that he had been discriminated against contrary to the provisions of The Equality Act (Sexual Orientation) Regulations (Northern Ireland) 2006 (‘the 2006 Regulations’) and/or The Fair Employment and Treatment (Northern Ireland) Order 1998 (‘the 1998 Order’), which prohibit direct or indirect discrimination on grounds of sexual orientation, political opinion or religious beliefs.

The County Court proceedings

The County Court considered whether Mr Lee had been discriminated against on grounds of sexual orientation and/or political opinion. It concluded that the McArthurs had directly discriminated against Mr Lee on the grounds of ‘his sexual orientation’ (para 13) and on the grounds of his ‘religious belief or political opinion’ (para 14).

In respect of the sexual orientation claim, the County Court accepted that the McArthurs’ deeply held religious beliefs were genuine, but it noted that Ashers was not a religious organisation, rather a commercial business run for profit. Whilst the 2006 Regulations provide some exceptions for religious organisations, Christian-owned businesses are excluded from such exceptions. As a consequence, the County Court concluded that the actions of the McArthurs could not be justified under the 2006 Regulations.

In respect of the political beliefs claim, the County Court held that, in the context of the ongoing debate on same-sex marriage in Northern Ireland, Mr Lee’s support for same-sex marriage amounted to a political opinion. Thus, in refusing to fulfil Mr Lee’s order the McArthurs had directly discriminated against him in a way that was incompatible with the 1998 Order.

The McArthurs invited the County Court to ‘read down the provisions of the 2006 Regulations and the 1998 Order in a manner which was compatible with their Convention rights’ under section 3 of the Human Rights Act or, if that was not possible, ‘to disapply the relevant provisions of the 2006 Regulations and the 1998 Order’ (para 15). In this respect, the County Court accepted that Article 9 of the Convention was engaged in this case, but it ultimately concluded that whilst the McArthurs ‘were entitled to hold their genuine and deeply held religious beliefs and to manifest them, they could not do so in the commercial sphere if this would be contrary to the rights of others’ which included Mr Lee’s right not to be discriminated against on the grounds of his sexual orientation (para 16). The County Court further held that the McArthurs had not been required to ‘support, promote or endorse’ Mr Lee’s views and it therefore concluded that Article 10 was not engaged in this case (para 18).

The Court of Appeal proceedings

The Court of Appeal confirmed the findings of the County Court and found that there had been associative direct discrimination against the applicant on the ground of sexual orientation (that is, the applicant had been discriminated against on the basis of his association with the gay and bisexual community). Moreover, the Court of Appeal agreed with the County Court that the McArthurs had not been in any way required to promote or support same-sex marriage by fulfilling Mr Lee’s order (para 22).

The Supreme Court proceedings

The UK Supreme Court (UKSC) disagreed with the lower courts, and it unanimously held that the defendants’ refusal to fulfil Mr Lee’s order did not constitute unlawful discrimination.

In respect of the sexual orientation claim, the UKSC disagreed with the County Court, and it held that Ashers had cancelled the order not on the basis of Mr Lee’s actual or presumed sexual orientation, but because they oppose same-sex marriage. The UKSC further disputed the Court of Appeal’s finding that Ashers had cancelled the order because the applicant was likely to associate with the gay and bisexual community, of which the McArthurs disapproved. Indeed, the UKSC established that ‘[i]n a nutshell, [the McArthurs’] objection was to the message and not to any particular person or persons’ (para 27).

The UKSC further determined that the McArthurs’ objection was to ‘being required to promote the message on the cake’ and ‘the less favourable treatment was afforded to the message not to the man’. Thus, it concluded that Ashers had not discriminated against Mr Lee because of the owners’ religious beliefs (para 30).

In respect of the political beliefs claim, the UKSC did not exclude that Mr Lee may have been discriminated against on the basis of his political opinions. However, the UKSC went on to consider the McArthurs’ rights under Article 9 and Article 10 of the Convention upon the effect of the 1998 Order, and it found that the 1998 Order ‘should not be read or given effect in such a way as to compel providers of goods, facilities and services to express a message with which they disagree unless justification is shown for doing so’ (para 34). Since no justification had been shown for justifying the compelled speech, the UKSC held that there had been no unlawful discrimination and dismissed Mr Lee’s claim for breach of statutory duty.

In conclusion, the UKSC allowed the defendants’ appeal and set aside the declarations and order for damages made by the County Court.

Complaints to the Court

The applicant claimed that the decision of the UKSC to dismiss his claim for breach of statutory duty violated his rights under Article 8, Article 9, and Article 10, alone and taken in conjunction with Article 14 of the Convention.

The Court’s assessment

The Court started by considering whether the applicant had exhausted all domestic remedies before lodging his application under the Convention.

The Court noted that the applicant had formulated his claim with reference to the 2006 Regulations and the 1998 Order, without expressly invoking any of his Convention rights at any point in the domestic proceedings. In this respect, the Court reiterated the subsidiary nature of the Convention machinery and the general principle that any complaint presented before it ‘must have been aired, either explicitly or in substance, before the national courts’ (para 68).

The Court took note of the applicant’s argument that a) he had raised his Convention arguments ‘in substance’ in domestic proceedings, since the 2006 Regulations and the 1998 Order had been enacted to protect his rights under Articles 8, 9, 10 and 14 of the Convention; and b) that the violations complained of before the Court had ‘only crystallised with the handing down of the judgment of the Supreme Court’ (para 69).

Nevertheless, the Court was not persuaded by these arguments for two key reasons.

First, the Court held that the relevant provisions in the 2006 Regulations and the 1998 Order cannot be said to ‘protect consumers’ substantive rights under Articles 8, 9 or 10 of the Convention’ (para 70). The Court acknowledged that the 2006 Regulations and the 1998 Order had been enacted in order to protect the Convention rights of consumers, but it also noted that those provisions, unlike the Convention, protect consumers in a ‘very limited way’ and concern only discrimination in access to goods and services (para 70). On this basis, the Court denied that the applicant has raised his rights protected under Article 8, Article 9 and Article 10 in substance during the domestic proceedings.

In respect of whether the applicant had invoked Article 8, Article 9 and Article 10 taken together with Article 14, the Court acknowledged that the applicant had raised the issue of whether he had been discriminated against on the basis of his sexual orientation and/or political beliefs in the domestic proceedings. However, the Court reiterated the ancillary nature of Article 14 and recalled that ‘there can be no room for its application unless the facts at issue fall within the ambit of one or more substantive Convention rights’ (para 72). The Court did not exclude that the facts of the case could fall within the ambit of Convention rights, but it ultimately held that by relying solely on domestic law the applicant had ‘deprived’ the domestic courts of the opportunity to consider themselves whether the facts of the case engaged his rights under Article 8, Article 9 and Article 10 before lodging his application with the Court (para 74).

Second, the Court noted that domestic courts had been tasked with balancing the applicant’s rights under the 2006 Regulations and the 1998 Order against the McArthurs’ rights under Articles 9 and 10 of the Convention, but at no point had the domestic courts been tasked with balancing the applicant’s Convention rights against the McArthurs’ Convention rights. Notably, the Court compared the approach followed by the applicant throughout the domestic proceedings with that followed by the McArthurs and concluded that the applicant had not provided a ‘satisfactory explanation’ for not advancing his Convention rights before domestic courts (para 77). Unlike the applicant, the McArthurs had effectively relied on their Convention rights throughout the domestic proceedings and had asked the courts to either read down the provisions of the 2006 Regulations and the 1998 Order in a manner which was compatible with their Convention rights or, if that was not possible, to disapply the relevant provisions of the 2006 Regulations and the 1998 Order.

On this basis the Court held that in cases where ‘the applicant is complaining that the domestic courts failed properly to balance his Convention rights against those of another private individual, who had expressly advanced his or her Convention rights throughout the domestic proceedings, it is axiomatic that the applicant’s Convention rights should also have been invoked expressly before the domestic courts’ and it concluded that ‘[i]n choosing not to rely on his Convention rights, the applicant deprived the domestic courts of the opportunity to consider both the applicability of Article 14 to his case and the substantive merits of the Convention complaints on which he now relies’ and he invited the Court to ‘usurp the role of the domestic courts by addressing these issues itself’ (para 77).

In conclusion, the Court considered that the applicant has failed to exhaust domestic remedies in respect of his complaints under Articles 8, 9 and 10 of the Convention, read alone and in conjunction with Article 14.

Two brief considerations

A peculiar interpretation of the relationship between the Human Rights Act 1998 and the Convention

This decision hands down a peculiar interpretation of the relationship between the Human Rights Act 1998 and the Convention, that no doubt will draw criticism and raise debate.

According to the Court’s reasoning, when reading and giving effect to primary and subordinate legislation domestic courts seem required to take into account the Convention rights of the litigants only if the litigants themselves invoke those rights.

When reading the Court’s decision, one may reasonably get the impression that under the Human Rights Act 1998 domestic courts are not allowed to consider litigants’ Convention rights motu proprio. However, section 3 of the Human Rights Act 1998 does not mention any such constraint and simply states ‘[s]o far as it is possible to do so, primary legislation and subordinate legislation must be read and given effect in a way which is compatible with the Convention rights’.

Nothing in this provision indicates that considerations of the relationship between domestic legislation and the Convention are conditional on the arguments made by litigants. On the contrary, a plain reading of this provision suggests that, whenever it is possible to do so, domestic courts should read and give effect to primary and secondary legislation in a way that is compatible with the Convention of their own accord.

As a consequence, it remains unclear why the Court assumed that the UKSC could not assess motu proprio whether domestic legislation had been interpreted in a way that adequately protected Mr Lee’s Convention rights.

A cautious approach?

This decision arguably signals the Court’s intention to maintain a cautious approach on complaints concerning a ‘clash’ between the right of individuals to freedom of religion and the right of LGBTIQ individuals to not be discriminated against in accessing goods, facilities, and services.

Whilst not examining the merits of the applicant’s complaint, the Court acknowledged that a balancing exercise of the applicant’s Convention rights against the McArthurs’ Convention rights would be ‘a matter of great import and sensitivity to both LGBTIQ communities and to faith communities’, especially in the context of Norther Ireland where ‘there is a large and strong faith community, where the LGBTIQ community has endured a history of considerable discrimination and intimidation, and where conflict between the rights of these two communities has long been a feature of public debate’ (para 75).

As a general principle, the Court held that similar disputes must be resolved ‘with tolerance, without undue disrespect to sincere religious beliefs, and without subjecting gay persons to indignities when they seek goods and services in an open market’ (para 75).

However, the Court also reiterated that in the light of the ‘heightened sensitivity of the balancing exercise in the particular national context’ the domestic courts would be better placed than the international judge to strike the balance between Mr Lee’s competing Convention rights and the McArthurs’ Convention rights (para 76).

On this basis, it seems likely that, even if Mr Lee’s complaint had been declared admissible, the Court would have deferred to the margin of appreciation available to domestic authorities and confirmed the findings of the UKSC.

Comments

Post a Comment