40th anniversary of gay law reform in Northern Ireland

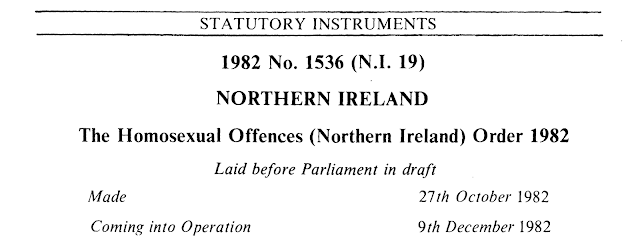

Forty years ago today, on the 27th October 1982, the Privy Council of the United Kingdom made the Homosexual Offences (Northern Ireland) Order 1982.

With Her Majesty The Queen on a Commonwealth visit to Tuvalu, it was Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother and Her Royal Highness The Princess Margaret who, as the Counsellors of State in Council, made the Order.

The purpose of the Order, which came into operation on the 9th December 1982, was to extend to Northern Ireland the same reform of the law relating to “homosexual acts” that had happened in England and Wales in 1967 and in Scotland in 1980.

As a consequence, the Order ended the complete criminalization of sexual acts between men in Northern Ireland by partially decriminalizing consensual sexual acts in private between two men of or over the age of 21 years.

The European Court of Human Rights

The Order was the direct result of the judgment of the European Court of Human Rights in Dudgeon v the United Kingdom that was promulgated in October 1981.

In that judgment the European Court of Human Rights had agreed with the applicant, Jeffrey Dudgeon, that the restriction imposed on him as a gay man, by the laws criminalizing all sexual acts between men, amounted to a violation of the right to respect for private life protected by Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights.

An event was held last year to mark the 40th Anniversary of Jeffrey Dudgeon’s victory in the European Court of Human Rights, and to acknowledge its global significance as the first successful “gay rights” case under international human rights law.

Parliamentary debates

Two days before the Privy Council made the Order, a draft of the Order was debated by the House of Commons.

The Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, James Prior MP, introduced the debate, emphasising that the United Kingdom had undertaken to abide by decisions of the European Court of Human Rights and, as such, that the Government believed that it must stand by its international obligations and abide by the Court’s judgment in the Dudgeon case.

Strong opposition to the Order was advanced by Rev. Ian Paisley MP, who argued that the Order “attacks the very cement of society” and “weakens not only the moral but the social fibre of society”, and by Rev. Martin Smyth MP – the MP for the constituency in which Jeffrey Dudgeon lived – who bemoaned Parliament “establishing a pattern as we yield to the gay rights lobby and cry out for equal opportunities”.

Enoch Powell MP also opposed the Order, principally on the grounds that the Government was acting under the “external compulsion” of the European Convention on Human Rights and, on this basis, that the House of Commons should not legislate “under duress” and impose “judge-made law” – an argument that Leo Abse MP described as an “infantile reaction”.

The House of Commons overwhelmingly supported the Order, voting Ayes 168 and Noes 21 to approve it.

A day after the House of Commons debate, the House of Lords debated the Order.

The tone of the Lords debate was overwhelmingly supportive. The Minister of State for Northern Ireland, the Earl of Gowrie, stated that the Order “will not have the adverse effect feared by some on the moral fabric of Northern Ireland society”.

Lord Elystan-Morgan, who regarded the Order as a measure of “compassionate tolerance” rather than “slack permissiveness”, stated:

It is right that the citizens of Northern Ireland should enjoy the same rights in this respect as the citizens of the United Kingdom. It is right also that we should place our law in line with stern international obligations.

Lord Foot agreed, arguing:

what I find intolerable is that, in a basic matter affecting human behaviour, conduct which is permissible in one part of the United Kingdom should be liable to draconian penalties in another part. That is something which, as a matter of principle, I do not think can ever be justified.

The Lords agreed to approve the Order without division.

The legal effect of the Order

In essence, the Order decriminalized homosexual acts – acts of “buggery” and “gross indecency” between men – in line with the then law of England and Wales.

A homosexual act ceased to be a criminal offence if it was done “in private” – which did not include acts committed when more than two persons took part or were present, or acts committed in a public lavatory – between men who consented and had attained the age of 21 years. The then “age of consent” for different-sex sexual acts (other than buggery) and female same-sex sexual acts was 17 years.

The Order contained the same restrictions on consensual homosexual acts committed by adults that were then in force in England and Wales. These included provisions enabling such homosexual acts to remain offences under service (armed forces) law in force at the time, and for such homosexual acts to remain an offence if done on a merchant ship by members of crew.

The Order created the offence of “procuring others to commit homosexual acts”, which made it an offence for a man to procure another man to commit with a third man an act of buggery, even when the act of buggery would not in itself be an offence.

And the Order altered the punishments for certain homosexual acts and, in some cases, increased the maximum punishment.

The Order today

At the time it was being approved by Parliament, Leo Abse commented on the “absurdities” of the Order:

How absurd it is to say that the age of consent must be 21. How absurd it is that we should pass an order under which a ménage à trois can take place between a man and women but be outlawed when all men are involved. How absurd it is that the law should say that a man on a merchant ship can have a relationship with a passenger but that he cannot have such a relationship with a fellow sailor without an offence being committed.

However, whilst the Order represented only partial reform of the law relating to homosexual acts it set in motion a process of legal reform that has continued to the present day.

Since it was made, the Order has been amended and revoked many times by Parliament over the course of 40 years of law reform.

For example, the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994 amended the Order to lower the “age of consent” for homosexual acts from 21 to 18 years, and revoked the restriction on homosexual acts in the armed forces and on merchant ships.

The Sexual Offences (Amendment) Act 2000 further amended the Order to create an equal “age of consent” of 17 years (later reduced to 16 years).

Several provisions in the Order were revoked by the Sexual Offences Act 2003 as part of a package of law reform that led to the abolition of the offences of buggery and gross indecency.

Only one substantive offence in the Order remains in force which is the offence of “premises resorted to for homosexual practices”, and the Order continues to make provision for premises to be treated as a brothel “if people resort to it for the purpose of lewd homosexual practices”.

Disregards and pardons

Parliament has recently taken several steps to address the wrongs done to people in Northern Ireland who were convicted or cautioned under now abolished homophobic laws.

The Policing and Crime Act 2017 enabled individuals convicted of, or cautioned for, certain abolished homosexual offences to apply to have a conviction or caution disregarded and, if successful, to be pardoned.

Posthumous pardons have also been granted to those convicted of, or cautioned for, certain abolished homosexual offences, under certain conditions, extending back to 1634.

The Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act 2022 ensures that disregards and pardons will be available to members of the armed forces who were convicted under service law for consensual same-sex sexual acts that would not be an offence today.

Comments

Post a Comment